a decolonial healing justice

The mainstream approach to justice as we know it, adversarial or inquisitorial, has its roots in colonial structures and systems. Two sides to a case are pitted against one another, and the demonstration of satisfactory evidence with clever wordsmithing decides who wins. In around the second half of the 18th century, British advocates ushered in the adversarial court system that has come to operate in most countries world over. This system does not interrogate power, does not prioritise healing, and does not recognize context. The adversary judicial system is so deeply engrained in our global understandings of justice that we almost never question it.

The proliferation of the adversarial system accompanied colonisation. This mechanism crafted the judicial apparatus as a “power” within the state. To understand the colonial connotations of this template, the Westphalian History of a state is relevant. According to the Westphalian system, the political order in international law and relations is such that each state has exclusive sovereignty over its territory, and is the monopolist of the ability to conduct warfare. The Peace of Westphalia ended the Thirty Years' War (1618 to 1648) and Eighty Years' War (1568 to 1648), and the principle underlying it has found mention in the founding documents of the post-World War II world - the UN Charter. The Eighty Years' War was a prolonged struggle for the independence of the Protestant-majority Dutch Republic (the modern Netherlands), supported by Protestant-majority England, against Catholic-dominated Spain and Portugal. The Thirty Years' War was the most deadly of the European wars of religion, centred on the Holy Roman Empire.

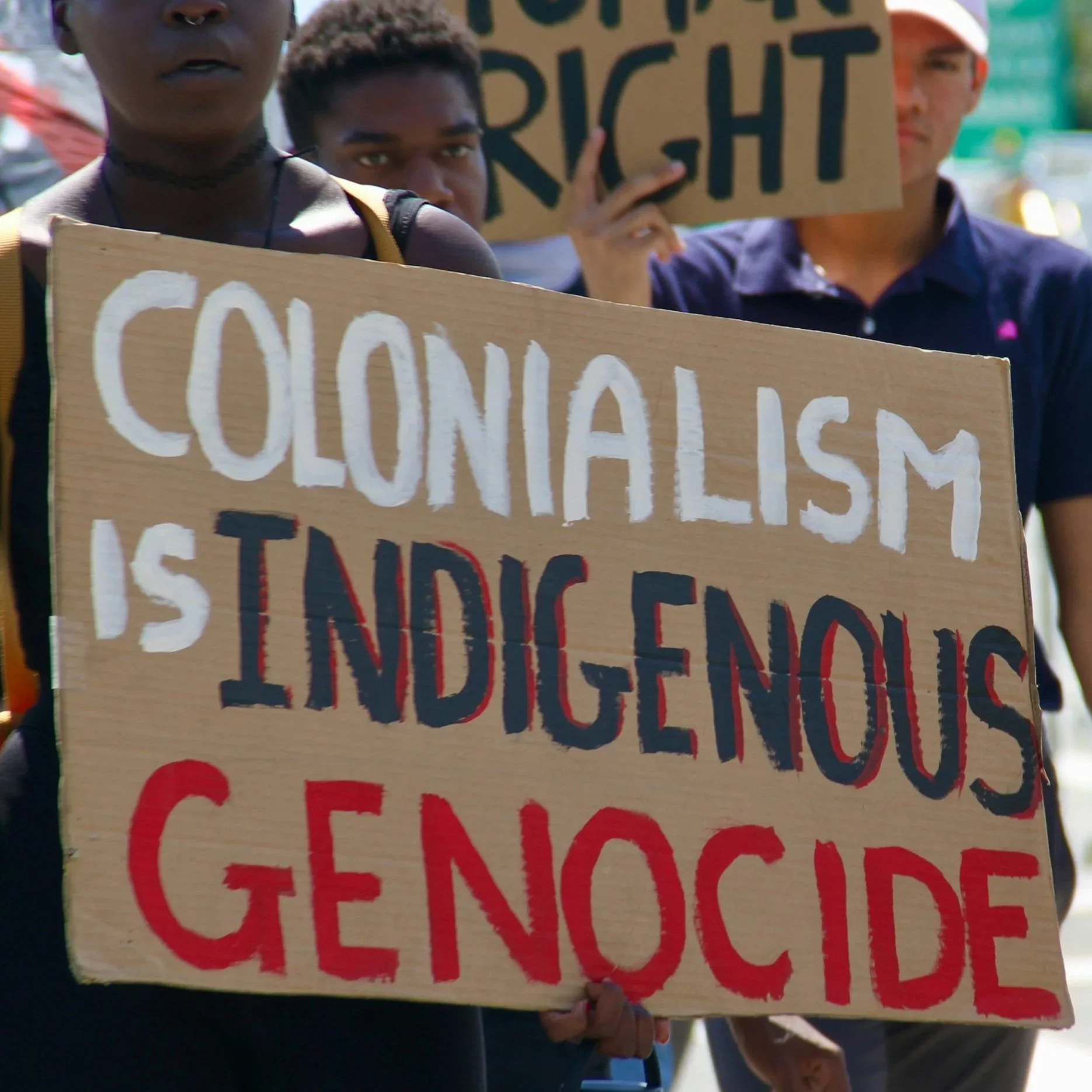

In one fell swoop, the Westphalian system normalized a template that colonialism exported world over, and in the steady movement toward decolonization, the system was entrenched as the “ideal” form of international relations. Boundaries and borders in most parts of the colonized world were drawn by colonizers, policies of divide and rule that normalized and re-emphasized divisions in each society with deeper roots crystallized in post-colonial governance mechanisms, and indigenous governance was almost entirely either wiped out, or considered anti-state for asserting self-determination and ethno-nationalism. The patriarchal ways of this system offered neither room for substantive engagements for women and non-binary people, nor considered marginalization on variety of grounds an area desperately in need of transformation.

There has been no attempt at healing and doing justice for colonialism, and the harm caused by the elite and the privileged to the marginalized before colonialism – for example, the caste system in India is older than colonialism and has endured as a standing example of systemic oppression that only gained affirmation after colonialism. Against this backdrop, states are interacting as colonizers or the formerly colonized – and these two compartments are not watertight, because as a variety of contexts show, the colonized can also be the colonizer. This is particularly true given that the sovereign state was the goal or the end victory for anticolonial movements. However, though they adopted the Westphalian template as a self-determined, positive outcome of their efforts to overthrow colonialism, in sharp contrast, many of these postcolonial states became perpetrators of large-scale human rights violations within the territories they fought for.

In the words of Sahla Aroussi, justice is inherently “locally relevant and context specific.” The heavy focus on procedure and punitive justice has meant that there is a limited frame of justice - both in its definition and in the apparatus available for its provision. Within this scope, a survivor is neither heard nor included in framing the idea of justice. Within this scope, the “solution” to harm is punishment - a carceral, limiting approach that has its roots in a quick-fix solution rather than a transformative pathway. Within this scope, justice is done for the powerful. The “wrongdoer” is an anomaly. The law is a tool of control. Society is policed and subject to surveillance. The cost of security is violence.

Questions linger: Whose idea of justice is key? Whose idea of security counts? Who experiences this justice in ways that are advantageous? Does healing come from punitive approaches? What does healing look like?

This is not to mean that domestic and traditional means of doing justice have been entirely successful. While it is not ideal to gloss over any one kind of judicial apparatus as the ideal solution, the point to be borne in mind is that the idea of “justice” should be defined by those who seek it. For justice to be efficient and responsive, so that it serves the needs of the survivors while also addressing impunity, as Sahla Aroussi notes, it is important to “understand not only how justice is conceptualized in the local context,” but to also understand what “influences survivors’ perceptions of justice.”

One way to do this is to shift out of a colonial framework for justice – into a decolonial healing justice approach. This calls for imagination, for recognizing that justice is more than punishment, that justice can be true justice if the survivor seeking it is a stakeholder in its conceptualization and delivery. This calls for moving away from business as usual. Decolonial healing justice can bring in alternative ways to both imagine and implement justice. It can help us recognize the local, contextual realities informing the need for justice, and most of all, shift the very focus of justice in itself.